Preventing Fentanyl Overdoses by Rethinking Drug Testing

- Ashish Bhatia

- Jun 12, 2023

- 9 min read

Updated: Jul 3, 2023

FC'22 Member Julia and Evan

Working with a controversial and undervalued problem

Drug usage is one of the most taboo topics in the United States today. Despite how little we talk about this problem, it has become exceedingly obvious as of late how severe the issue has become. According to the American Addiction Centers, 2 in 5 young adults in the age range of 18 - 25 have used an illicit drug in the past year. Even more shocking is the fact that fentanyl overdose is the #1 cause of death for Americans ages 18 - 45, exceeding even COVID in the past two years. In a way, this could be seen as the most critical, life-threatening problem facing young and middle-aged adults in the United States.

Our journey started last spring in one of Professor Bhatia’s Patterns entrepreneurship classes. In that semester, we engaged in design thinking to develop a clearer understanding of the fentanyl epidemic from the perspective of the user and ideate solutions that best fit their needs. We came away with a potential product that could play a key role in lessening and hopefully ending the fentanyl epidemic for recreational users.

The following semester, both Julia and I were entering our final year at NYU Stern, and we both wanted to take the opportunity to work on this issue that we see as vitally important and life-saving to communities that are close to us. We decided to continue on this project outside of the classroom.

Becoming Aware of the Problem

I was first introduced to the magnitude of this problem when I became flooded by news articles about the fentanyl epidemic around a year ago. I was shocked to learn that it was accountable for more deaths in the 18 - 45 age group than COVID! Despite how much I was seeing it in the news, no one I knew was talking about the problem. Everyone seemed to consider a distant issue that was affecting communities that were far away and removed from my social circles, which didn’t make much sense to me given the rise in fentanyl deaths in New York City, in particular!

When I presented this idea to a room full of my college peers, the reaction was lukewarm and hesitant. People were interested in offering advice, but very few wanted to have any role in a project like this one. Julia, however, was super enthusiastic about working together on this issue and recognized the severity of the problem we are looking at.

Taking this problem through design thinking

During the research phase of our design thinking process, we conducted interviews with as many people as we could to get an expansive, high-resolution view of the issue, including college students (both users and non-users alike), drug dealers, self-described ‘addicts’, and medical professionals.

From this hands-on research, several insights emerged that we thought to be profound and would later provide a trajectory for our proposed solution. We found that users are often stifled by a social stigma to test drugs at parties or in other drug-usage scenarios. Even if one is not embarrassed to do so, there are many barriers to obtaining reliable drug testing kits and safety supplies, and many people are unwilling to go through the” inconvenience” of ensuring that their drugs are not laced. Many of our interviewees reported a feeling of “herd-safety,” knowing that other people within their communities or circles were consuming drugs from the same dealer and batch.

Digging deeper, we uncovered some uncomfortable truths. Shockingly, we found that despite whatever barriers may exist, people are still going to use recreational drugs even if they are aware of the dangers of laced products. At the end of the day, most users (ranging from self-titled addicts to infrequent users) will only be stopped from using by one thing: certainty that a batch of drugs is laced. Furthermore, many people underestimate their own use and overestimate their safety precautions compared to others. At the same time, they are usually oblivious to not only the risk of drug contamination or overdose but also the existence and practicality of tests and safety supplies.

We learned some truly fascinating and concerning insights about behavior around drug use

We believe that these shortcomings in the drug testing space mostly derive from a lack of attention to the human behavior underlying drug usage. When beginning to prototype solutions for this problem, we challenged ourselves to think through the lens of these findings and create a solution that was derived from what we had learned about the nuanced psychology of recreational drug users. We wanted to ideate a solution that would: 1.) make testing in social settings less stigmatized and 2.) make access to testing materials simpler.

We asked ourselves where we can focus our time and be most effective in preventing fentanyl overdoses in recreational drug users. After all, drug usage is a far more complicated and multifaceted issue than fentanyl overdoses which have spanned generations. So we narrowed our focus to drug testing and how to make drug usage safer for recreational users.

At this point in the design thinking process, we came to the conclusion that our solution needed to be discrete and easy-to-use, but more importantly, it needed to normalize drug testing. Dare we say make it ‘cool’? We brainstormed a ton of ideas, ranging from apps that tracked overdoses in communities to subscription boxes that constantly resupply users with lifesaving materials like Narcan and testing strips.

Ultimately, we came to the conclusion that we needed to design a device that people would feel motivated to carry around with them to social settings where drug usage occurs, like bars, clubs, parties, and concerts.

Drawing inspiration from unlikely places

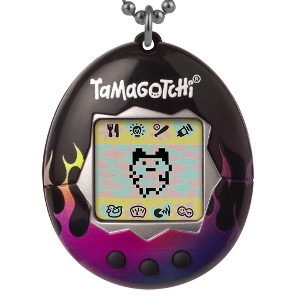

Sometimes inspiration comes from the strangest places - such as fad toys and accessories!

When trying to conceptualize what form our drug testing device will take, we asked ourselves what similar devices we have seen people carry around with them to social settings. More importantly, we wanted to make something that people carry around with them on their keychains. This is where the idea of a Tamagotchi style device for drug testing emerged. From here, we emerged with the idea for an electronic device that people can carry around on their keychains that is easy-to-use and can be interacted with in a game-like or toy-like manner. Beyond the motivation of drug-safety, this added an additional component of playfulness, stylistic appeal, and trendiness. We also drew inspiration from other fad toys and electronic devices that people carry around on their keychains that dually function as accessories and useful gadgets.

One major point of critique we’ve gotten has been around the desirability of this solution. Do our target customers care enough to go out of their way to both buy and carry something around something that is an accessory to drug use? While this is a critical assumption that we intend to test in the coming weeks, we have an idea based on the success of another product that our ‘Tamagotchi’ device will have traction: Narcan, a nasal spray that in the event of suspected overdoses. Whereas Narcan is a remedial and counteracting solution, our device is proactive and preventative.

Talking to experts

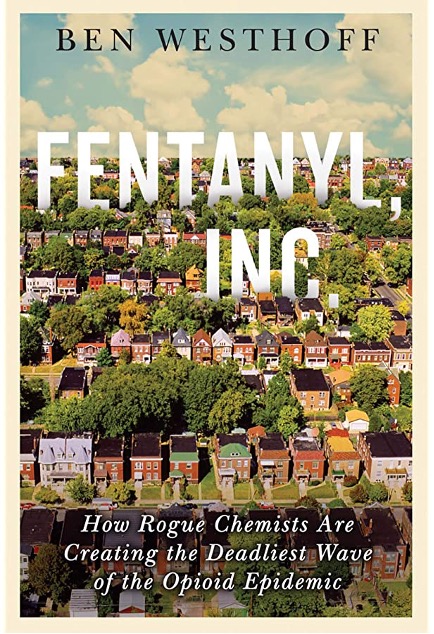

Having come up with the idea of a ‘Tamagotchi’ style device for drug testing, Julia and I were very excited to start developing this product and getting it into the hands of our target audience. First, however, on the advice of fellow members of the Founder Challenge, we decided to talk to some medical professionals and experts on the fentanyl crisis. So we blasted out cold emails to as many people as we could, and we secured two Zoom interviews with very knowledgeable experts. First, we spoke with Ben Westhoff, the author of ‘Fentanyl Inc’, one of the foremost experts on the fentanyl epidemic, from whom we learned several valuable lessons that changed the trajectory of our project. Firstly, we learned about the ‘chocolate chip cookie problem’ of drug testing, wherein batches will require several tests to ensure that it is uncontaminated. We also learned that most testing strips don’t test for fentanyl analogs (synthetic opioids with similar chemical structure to fentanyl that are just as deadly), which has become a key goal of our design. Most importantly, we told us about the legal gray area that drug testing products sit in, and that New York City is on the leading edge of harm reduction policies. In our interview with Dan Werb, an epidemiologist with expertise in drug policy, we become aware of the distinction between drug testing for opioids and an entirely separate category of drugs that are used in party and recreational settings. He also told us that there is a huge gap between high-tech drug testing solutions and those designed for consumer-usage.

We were fortunate to talk to some real experts on the topic and we are very grateful to them for taking the time to speak with us!

Perhaps the biggest lesson from these interviews, however, was not any particular insight into the behavior of drug users or a notion about the shortcomings of competitive products; rather, these two interviews revealed to us the sensitivity of this issue and the dramatic impacts that the fentanyl epidemics has had and continues to exert on the lives of users and their families and friends. While it had always been an unspoken truth between Julia and I that we cared little about the money or other vanities of startups and the entrepreneurial life, it became particularly clear to us that we have a high ethical standard in working in this space towards a solution for the fentanyl epidemic.

What is everyone else missing?

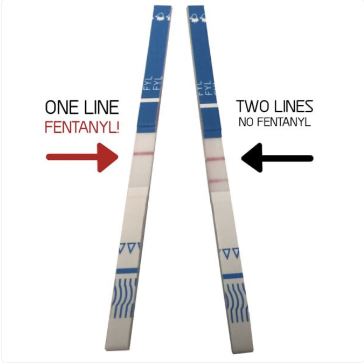

One critical part of our journey thus far has been assessing the ‘competition.’ There are several products on the market that test recreational drugs and are available for regular consumers outside of a laboratory setting. We tried to get a clear idea of the expanse of these products and how our idea shapes up to them. Most of these products are not easy to use. They would require individuals to test prior to going to a party, club, or other social setting and can take up to a few minutes to generate results. One of the most foundational insights we got from interviews, however, is that drug use occurs spontaneously, and that these at-home, difficult to use devices are not useful to target customers at the point-of-use. As you can see below, these devices and solutions, ranging from reagent kits to to strips, look more like medical devices you would see in a hospital rather than a gadget or device that young adults and recreational users would be likely to carry around to them in a social setting. We believe that these devices totally miss several key aspects of the consumer psychology behind drug testing.

As you can see above, the existing solutions are complicated to use and not aimed at unknowledgeable consumers.

Testing our idea with a low-fidelity prototype

Our long term vision is to create a “Tamagotchi’ style device that tests recreational drugs via electronics and reagent technology. However, we wanted to do a testing stage with our idea using a low fidelity prototype that captures all of the values we hope to bring to customers. In order to accomplish this, Julia and I decided to create a pill crusher which would allow users to easily test their recreational drugs in social settings. We intend to hand these out to interested users, as well as reach out to bars and clubs in NYC that currently offer out fentanyl test strips and ask them to hold this pill crusher device alongside the strips. This low fidelity prototype accomplishes our main goals: discretion, easy-of-use, and trendiness/‘cool-factor’. We hope to do a round of hypothesis testing with this prototype and use the results to modify our long term vision.

Roadblocks and obstacles

Our long term vision is to create a “Tamagotchi’ style device that tests recreational drugs via electronics and reagent technology. However, we wanted to do a testing stage with our idea using a low fidelity prototype that captures all of the values we hope to bring to customers. In order to accomplish this, Julia and I decided to create a pill crusher which would allow users to easily test their recreational drugs in social settings. We intend to hand these out to interested users, as well as reach out to bars and clubs in NYC that currently offer out fentanyl test strips and ask them to hold this pill crusher device alongside the strips. This low fidelity prototype accomplishes our main goals: discretion, easy-of-use, and trendiness/‘cool-factor’. We hope to do a round of hypothesis testing with this prototype and use the results to modify our long term vision.

What's next for UserFriendly?

At this point in the journey, we feel more motivated than ever to continue forward with the project. Past roadblocks, dead-ends, and obstacles have only galvanized our commitment to this problem. The encouragement we have received from fellow members of the Founder Challenge has been key in keeping us optimistic despite the hesitant and occasionally negative reactions we have received from people who know less about the issue. We want to prove that entrepreneurship is not just about flashy, scalable software in billion dollar industries. There is room for innovation and inspiration in all areas, even (especially) in something as taboo as recreational drug use. Despite the unique obstacles ahead of us, we are determined to develop this product and play a role in ending the fentanyl epidemic. We think that we’ve identified aspects of the problem that others have so far ignored and have used our distinctive viewpoints and knowledge to develop a solution that is smart, effective, and most importantly… user friendly.

You can reach out to us at emc761@nyu.edu and jcp598@nyu.edu.